Why do qigong if you’re a yogi

New moves that will make you feel like a million bucks

Yoga was my first love. Initially I remember how amazing the stretches felt to my over-contracted 23 year-old self. I first discovered yoga while fumbling through my mother’s photocopied yoga book from the 1970’s. At the time, I was living in Beijing, China, working as a photojournalist and suffering from multiple health issues including asthma, digestive problems and general fatigue. The basic yoga postures I practiced kindled awake a dormant sense of self-respect I had nearly lost for my body. I didn’t realize it them, but slowly yoga had started to shift my perspective about myself; everything sharpened into higher resolution.

Almost 20 years later I’m still amazed at how the postures and practice affect my body at every level. In this time I’ve also been fortunate to come across qigong – a Chinese energy cultivation practice – that I’ve found works in a surprising and delightfully complementary way with yoga.

My early forays into qigong happened after I moved to China in 1994 and before I tried yoga. I’ll confess that when I first learned them, the forms felt frumpy, static and not very sexy. My opinion was likely tainted as well by the notion that qigong was for old people in Chinese parks. It wasn’t until 2003, when I was introduced to the practice again by Matthew Cohen, that the process wowed me. Matthew is a highly respected yoga teacher, dancer, martial artist, and healer who lives and teaches in Venice, California. He teaches a fusion of yoga and qigong, and I found the combination complementary and potent. I invited him to teach at a yoga studio I had co-founded in Beijing with a fellow American yogini, Robyn Wexler.

Matthew’s introduction of wuji, yoga’s equivalent to tadāsana (mountain pose) was a game changer. In it, I felt centered, stable, rooted yet open to a movement of energy that I had not experienced in doing yoga poses. With my joints relaxed, center of gravity lower and spine curved delicately into the shape I probably started off feeling as a wee little embryo, I felt heat and a light hum of energy pulse through my limbs. I also felt the centers of my hands produce an uncanny amount of heat. Later I learned this is a good thing: the qi, or life force cultivated in a practice can be directed through spirit points located in the centers of the palms. These spirit points, called Working Palace, or laogong, are how qigong healers bring in and also transmit energy out from their own bodies to help nurture, heal or restore deficient qi in others.

What is qigong?

Qigong (chi kung) is an energy and intention-based practice with roots in Daoist (Taoist) beliefs. It’s the basis of Chinese martial art forms, Chinese medicine, and Chinese meditation. Jet Li, for example, practices qigong, as would many acupuncturists and Daoist priests. It is considered a healing art, and classified in China as a type of preventative medicine, or a means to help cure disease. Qi means “life force,” and gong means to cultivate or build. Thus qigong is the cultivation of life force, or energy. It works with the principle of “xing ming shuang xiu”– meaning the “body and spirit are equally refined and cultivated.”

Qigong is the cousin to yoga, the aunt of pilates, the sister of tai chi – all related in the common good to balance the mind, body and spirit

There are over 7,000 forms of qigong today. Tai Qi is perhaps the most well-known, stylized form of qigong. There are also forms named after locations such as Wu Dang, or in honor of animals and birds such as White Crane or Swimming Dragon. Many of the older forms of qigong are classified as the daoyin, or “stretching and breathing exercises.” These are sometimes referred to as Taoist Yoga, and include sequences such as the 5 Animal Frolics and the 8 Brocades. Later practices developed by the Shaolin Temple monks include the Muscle and Tendon Changing Classics. To me, the wide-ranging diversity of qigong forms suggests that there’s no right or wrong way to do a practice, and that the development is in line with Daoist notions of naturalism, spontaneity and self-trust.

The two practices compared

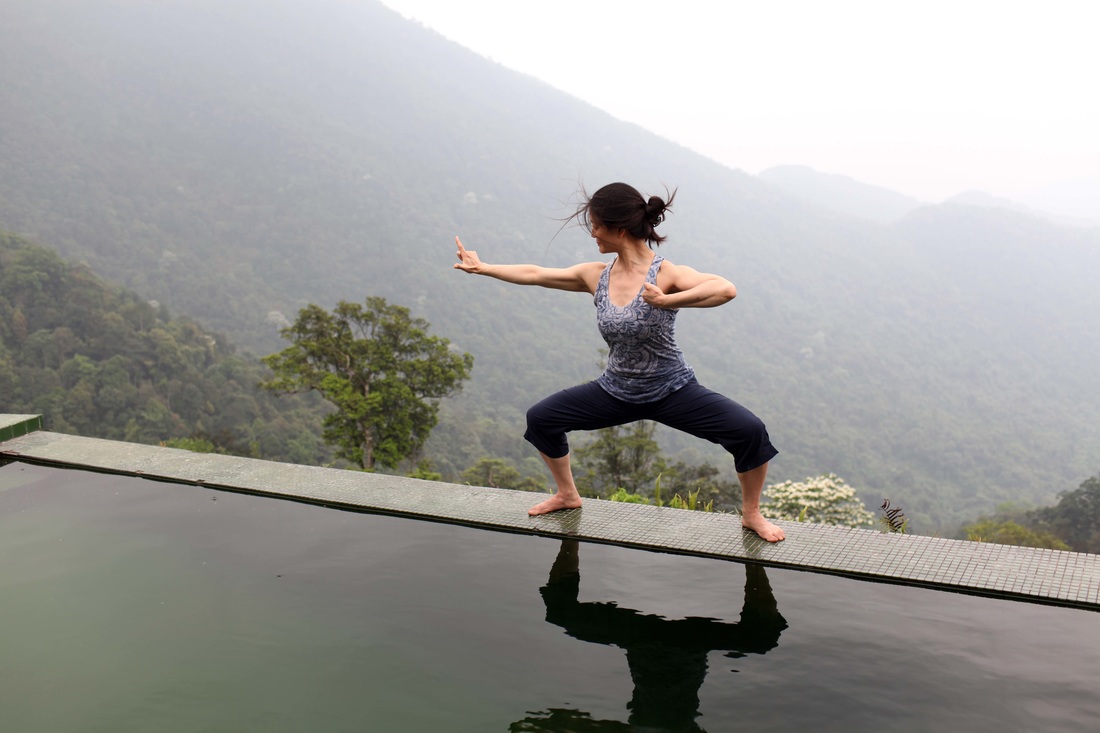

Speaking in quite general terms, yoga asanas tend to be more linear, focusing on stretching and extending the limbs and trunk in two directions. Think about triangle pose — how the top arm extends away from the bottom, and the spine lengthens from the tailbone back and the crown of the head forward. In qigong, there is a stronger emphasis on soft, round, circular movements that are like wind and water. Joint spaces are always relaxed, and the movements are often simple, slow and rhythmic. There is less focus on complex bodily positions, and more focus given to how the mind directs the vital energy, or qi, and intention. The intention is often on eliminating stagnant or diseased qi, and replacing it with healthy, vibrant qi. For example, one might inhale pure, healthy qi to an area of the body that feels weak, and exhale out the waste – and let it go as compost to the earth.

Also, with qigong, there is more of a focus on grounding and connecting with the earth. Active poses are often done with bent knees, allowing for the center of gravity to be closer to the ground. In yoga, unless the teacher is very conscientious to teach about the foundations and rooting through the earth, there can be a very strong upward flow of energy, or a sense of over prana-fication.

Blending traditions

Historically China has shown openness in embracing new traditions and practices as they migrate across continents and merchant trade routes. The Silk Road, for example, helped Buddhism flourish during the Tang Dynasty alongside existing Daoist and Confucian beliefs. Fusing and incorporating practices from different traditions from has been a rich source for creative growth in China – the Shaolin Temple monks, for example, are practicing Buddhists who have also captivated the world’s attention with their awe-inspiring martial arts forms.

Though yoga maintains a steady foothold in my daily practice, qigong is usually right there beside it. I find it offers me a slow, movement-based practice that enables me to focus my intention in specific ways to heal and rid my body of poisons – be it thoughts or physical sensations like tension or fatigue – and increase my levels of energy and healthy prana. I also find that as a teacher, I never get cold hands anymore! That is a huge bonus to giving assists in a yoga class; I doubt anyone likes to be touched by cold, clammy hands. For me, practicing yoga and qigong work like the fire and water. One gets me warm and spirited, the other quiet, fluid and soft.

By Mimi Kuo-Deemer